A Parent’s Guide to Torticollis in Newborns

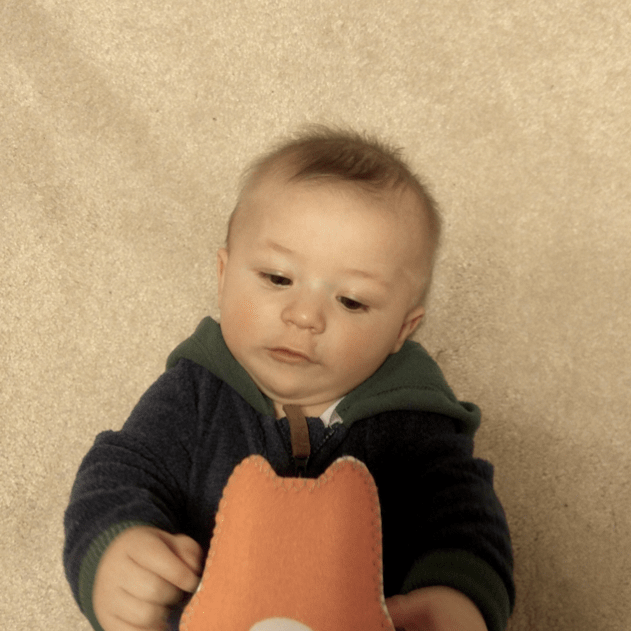

The medical term “torticollis” means “wry neck,” and is used to describe a baby that does not hold and move their head equally to the left and right sides. With torticollis, a newborn typically favors turning their head to one side and tilting it to the opposite side (aka turning to the right and tilting to the left or turning to the left and tilting to the right).

Why does my newborn favor one side?

The main culprit of infant torticollis is the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), a thick muscle that connects behind the ear and to the middle of the collar bone. When this muscle is tight, it remains in a shortened position with the head turned one way and tilted the other.

There are other ways that torticollis can present, because often nearby muscle groups get involved as well. Some babies may favor turning one way but do not have a head tilt. Some may have a head tilt but turn equally to the left and right. And some might turn and tilt to the same side. No matter the type of torticollis, early intervention via physical therapy is important to restore normal range of motion and posture.

Does infant torticollis go away on its own?

Waiting out torticollis in newborns is not recommended. Here’s why: torticollis is more than just a tight neck muscle. The head initiates and guides all of an infant’s movement patterns.

- When the head is not symmetrical, the torso is also held in a “C” shape. This affects how the baby is strengthening their truck muscles as they kick and wiggle. Once they start sitting, if this C-shaped posture persists, they are likely putting more weight on one side of their bottom than the other in an effort to balance their weight. When they start shifting in and out of sitting, they will learn to shift their weight over the hip with more weight on it. This is significant, because in order to learn to crawl, a child must shift their weight over both hips and lengthen and shorten their trunk in a left, right, left, right pattern.

- The SCM is connected to the collar bone. When the arm is raised, the collar bone rotates. If the SCM is tight, shoulder and arm movement can be restricted as well. To add to this dilemma, if a baby presents with typical torticollis, then they also favor turning away from this arm. When a baby is not looking at one hand, they are likely not using it, so their motor development of this arm and hand becomes delayed.

- Visual field is developing vastly in the early months of a baby’s life. The brain has an amazing way of making adaptations at this young age. If your baby is experiencing life with their head tilted to one side, the brain will adapt so that their visual interpretation of the world is not tilted. This can encourage a habitual head tilt that can persist for years, even when there is no longer a physical barrier.

- Secondary issues can arise when a child is not able to move freely. A child will learn to compensate for their limited neck range of motion and this can cause new areas of tightness to occur in the torso, pelvis, hips, and shoulders.

- Relearning skills is significantly more difficult than learning them correctly in the first place. Treating torticollis for a baby that is already sitting, rolling, and crawling presents with many challenges. The baby has adapted and compensated for their asymmetry and their neurologic system has learned that this is “normal.” Going backwards to retrain the neurologic system and create a new normal is a lot trickier than intervening early to make sure that normal movement patterns can be established from the get-go.

What if my baby with torticollis cries during pediatric physical therapy?

When a baby is crying through a PT session, something needs to change. It is 100% possible to have a tear-free 60-minute long torticollis pediatric therapy session. Ideally, your baby should be relaxed while stretching is performed. When a child is crying, they are tense, and stretching is ineffective. Additionally, their “fight of flight” system kicks in, and their higher-level learning systems are shut down.

- Stretching can easily be disguised as a cuddle. You and your PT just need to get creative.

- Stretching can also be performed from the bottom up to encourage increased tolerance for the baby. All babies are going to get irritated and tense when you grab their head and try to move it. Instead, keep your baby’s attention in one direction with a strong visual incentive and cleverly move their bodies to create a neck stretch. If your baby is lying on the ground, you can even brace the side of their face against your leg while you move their body. Your PT can help you effectively practice this method.

- Use active stretching more than passive stretching. An active stretch is when you encourage the baby to move their own head through incentives. A passive stretch is when you are physically positioning the stretch for them. Ask your PT how you can encourage your baby to actively stretch their own neck.

- Stand up, walk around! As we all know, babies love being held by a standing, rocking, swaying person. Work with your PT to create ways to hold your baby in which they are being stretched while you walk around.

- Ditch the baby containers. Equipment like Rock ‘N Plays, bouncy chairs, Bumbos, etc. will not do your baby any favors. Babies tend to fall into their torticollis when placed in equipment. Now, that being said, sometimes you need to put your baby somewhere so you can get things done. By all means, use the equipment so you can keep family life running smoothly. Just be aware that they should be used minimally and only as needed.

- This is the MOST important piece – treat the baby’s torso. Directly working on a baby’s neck is just a small piece of treating torticollis. If your PT is doing neck stretches while your baby lies flat on their back for an hour, it’s time to start asking for more. Remember earlier when we discussed how a head tilt places the baby in a “C” shape and this affects arm movement and hip position? All of this should be treated. If a baby cannot keep their body symmetrical, they certainly will not be able to keep their head held symmetrically. Don’t be afraid to ask your PT for more if need be.

What if my infant has a flat head?

Sometimes, torticollis can contribute towards a flattened area on the back of a newborn’s head. This flat spot can occur in the center or to the side, depending on how a child typically rests their head. The best way to observe a baby’s head shape is from above. Their head should appear round and symmetrical.

If you observe a flattened area on your baby’s head, the best time to be evaluated is at 4 months old because from 4-7 months there is an accelerated rate of growth of the skull bones. The faster the skull grows, the more quickly it can change for better or worse.

Once your baby’s head is measured, a cranial helmet may be recommended to improve their head shape. This is important, because the shape of the back of the head affects the shape of ear canals, eye sockets, the forehead, and cheek bones. If a child’s eyes are offset and not corrected early on, visual issues can develop and persist through life. In this instance a cranial helmet truly exemplifies an ounce of prevention trumping a pound of cure.

Physical therapy for torticollis in newborns

The head position of an infant is very important, because movement of the head guides movement of the rest of the body all the way down to their feet. When a child cannot achieve typical midline control of their head, asymmetrical movement patterns will develop throughout the entire body, creating delays in gross and fine motor development. Their head and face shape can also be affected.

So, if your baby can’t hold their head straight, be an advocate for your baby and request a physical therapy evaluation by a PT who has experience in working with newborns and torticollis. Earlier identification and intervention is always a win for both you and your child.

If you have concerns and would like your child to receive extra support, schedule an appointment with Milestone Therapy. Our pediatric physical therapists are happy to help!